Louise Sartor

"Kiss of Life"

Louise Sartor (b.1988, Paris)

Louise Sartor is currently in residence at the villa Médicis, Académie de France à Rome

Sartor studied stage design at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna (2011), at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (until 2012), and later at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris (until 2015). She devoted her graduation thesis to academic drawing, attended a “painting techniques” studio class, learned the chemistry necessary to master canvas preparation perfectly, reproduced Nicolas de Larguillière paintings in the Louvre, took classes in morphology and anatomical drawing ... in short did everything but what is presumably expected from a contemporary artist.

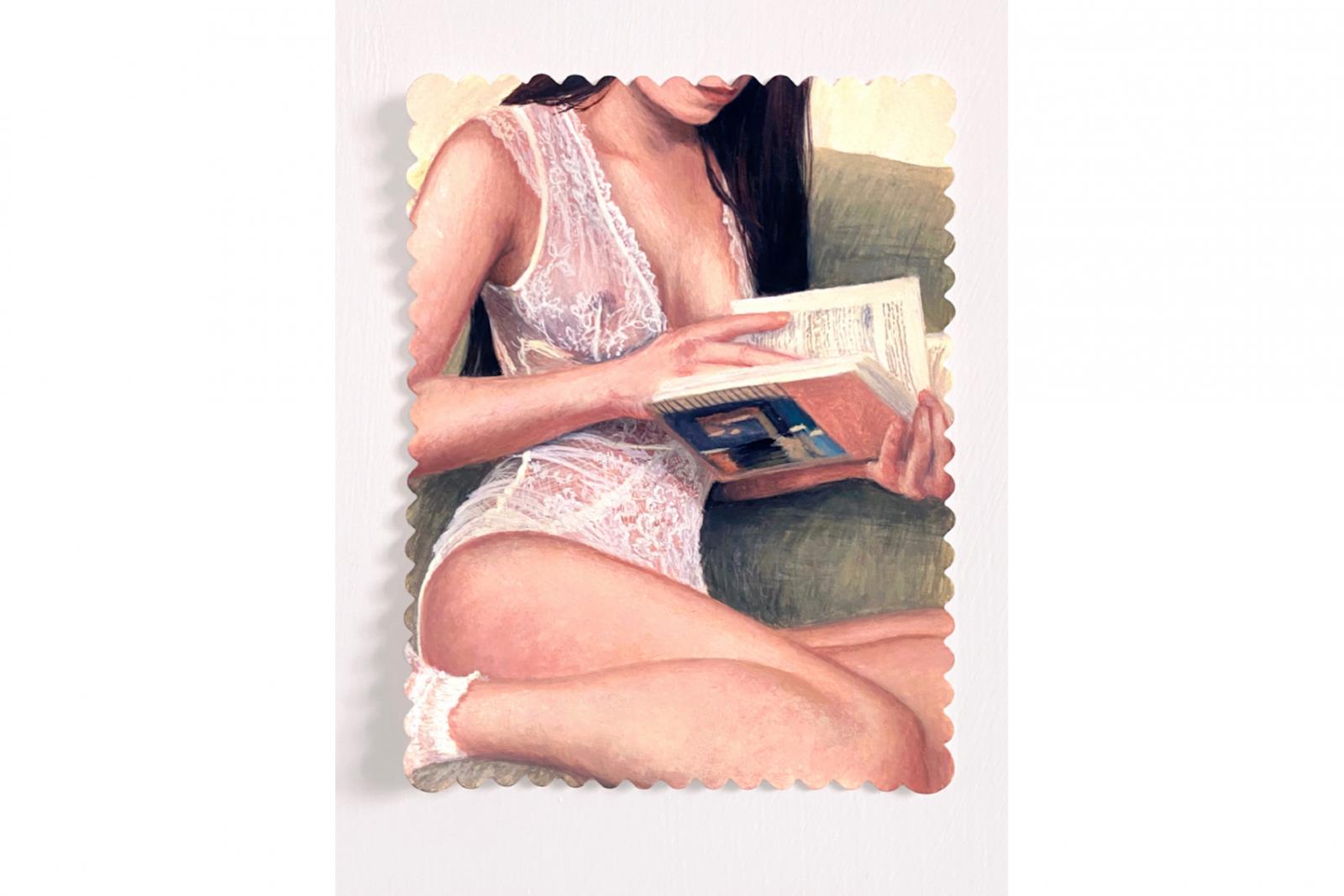

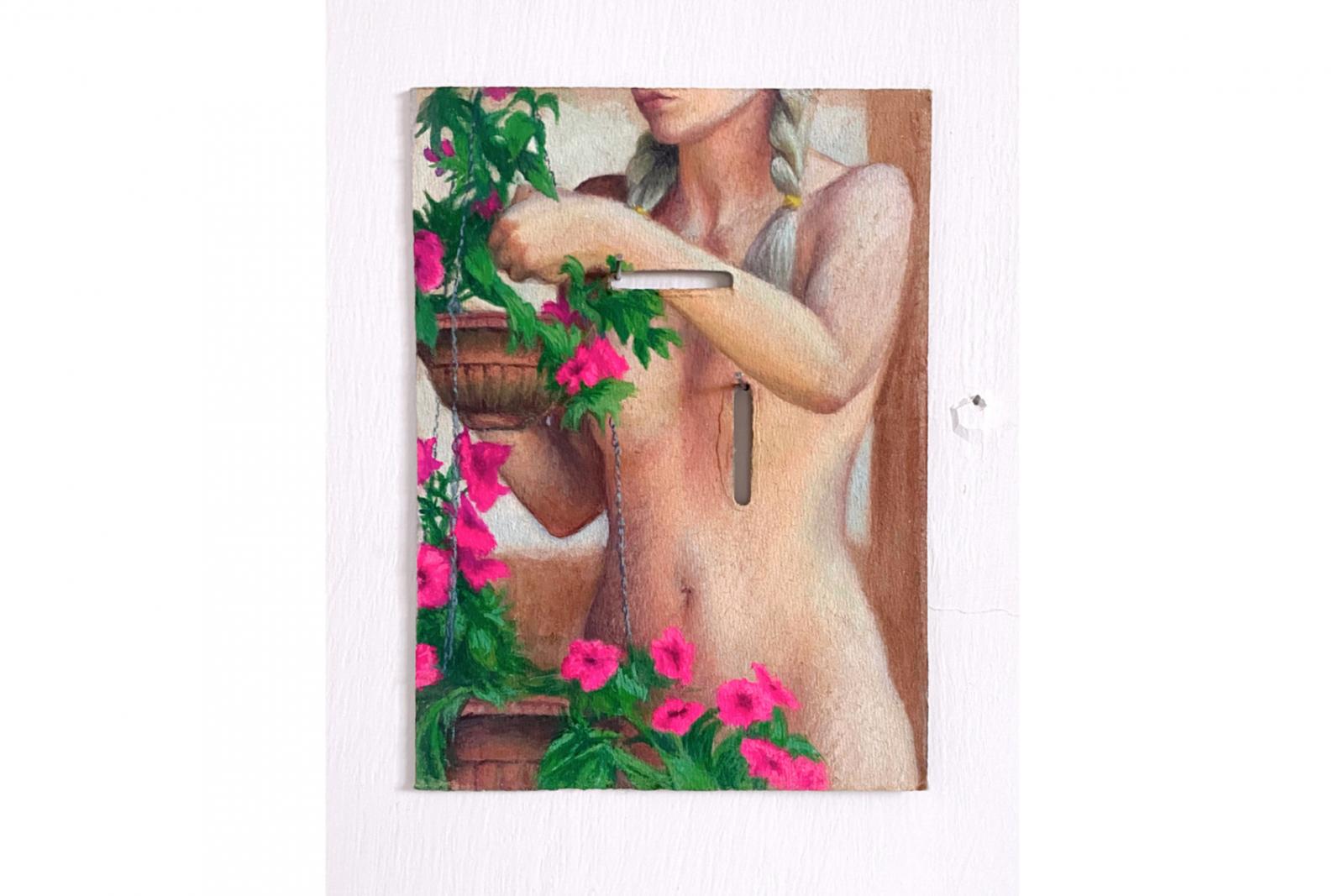

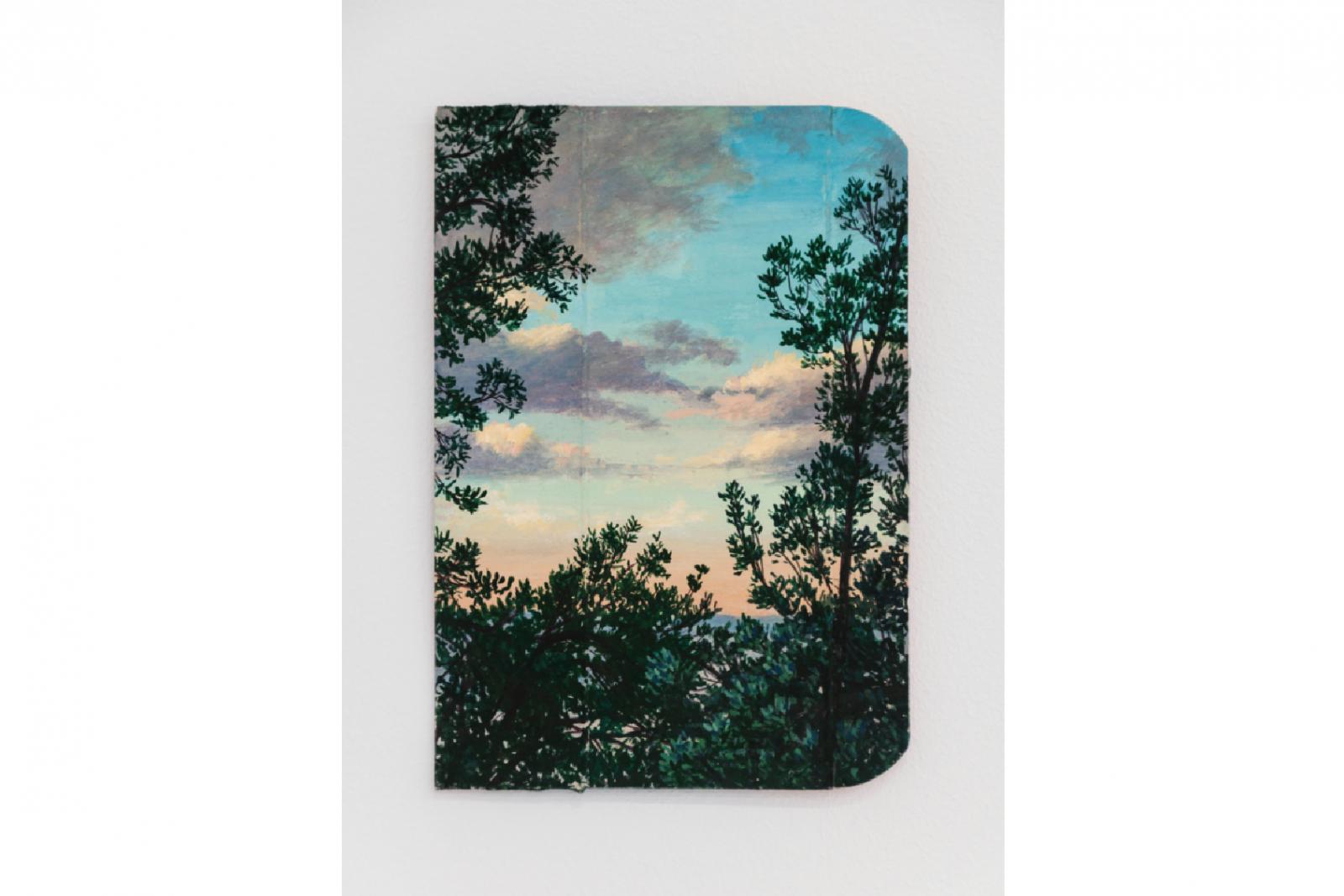

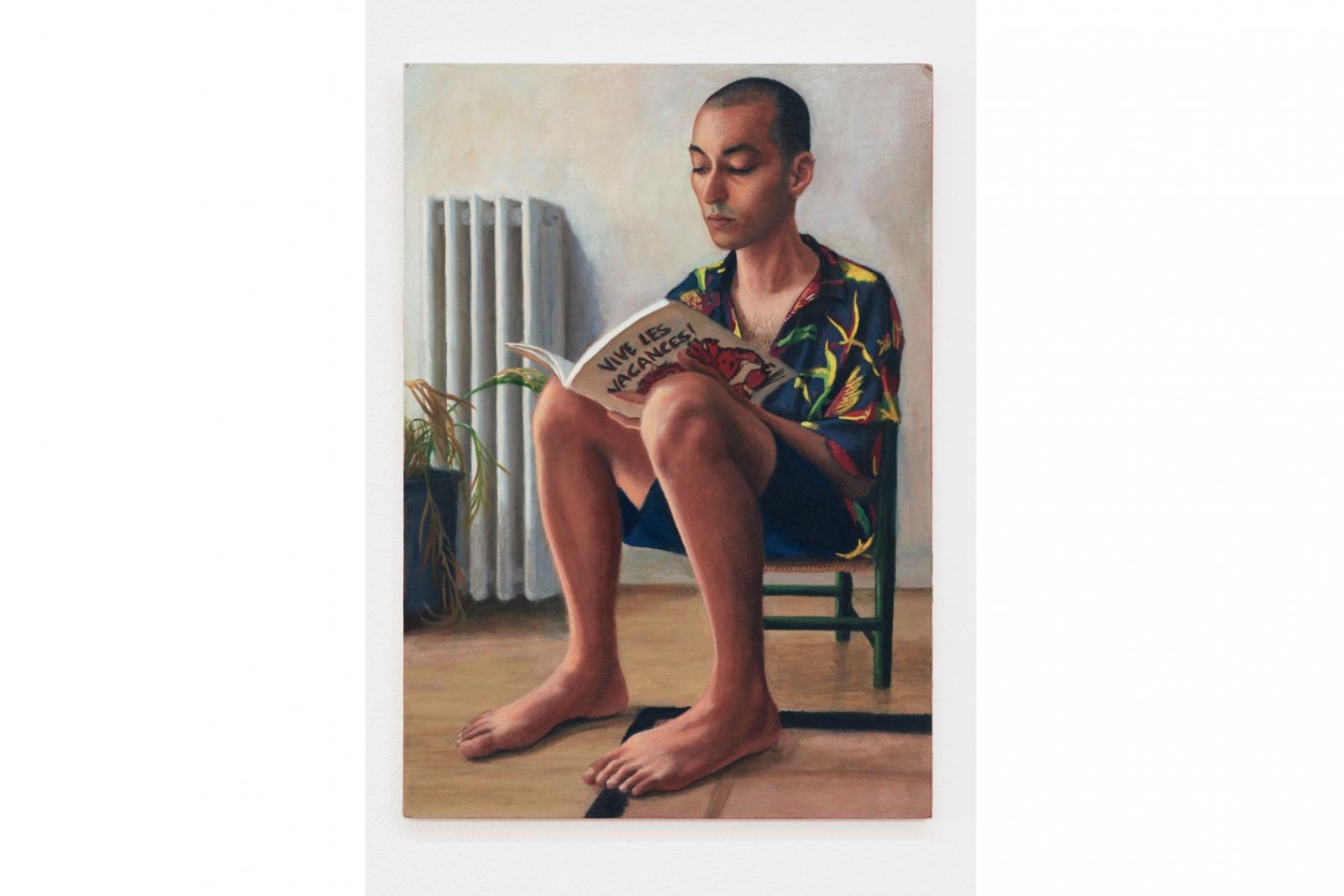

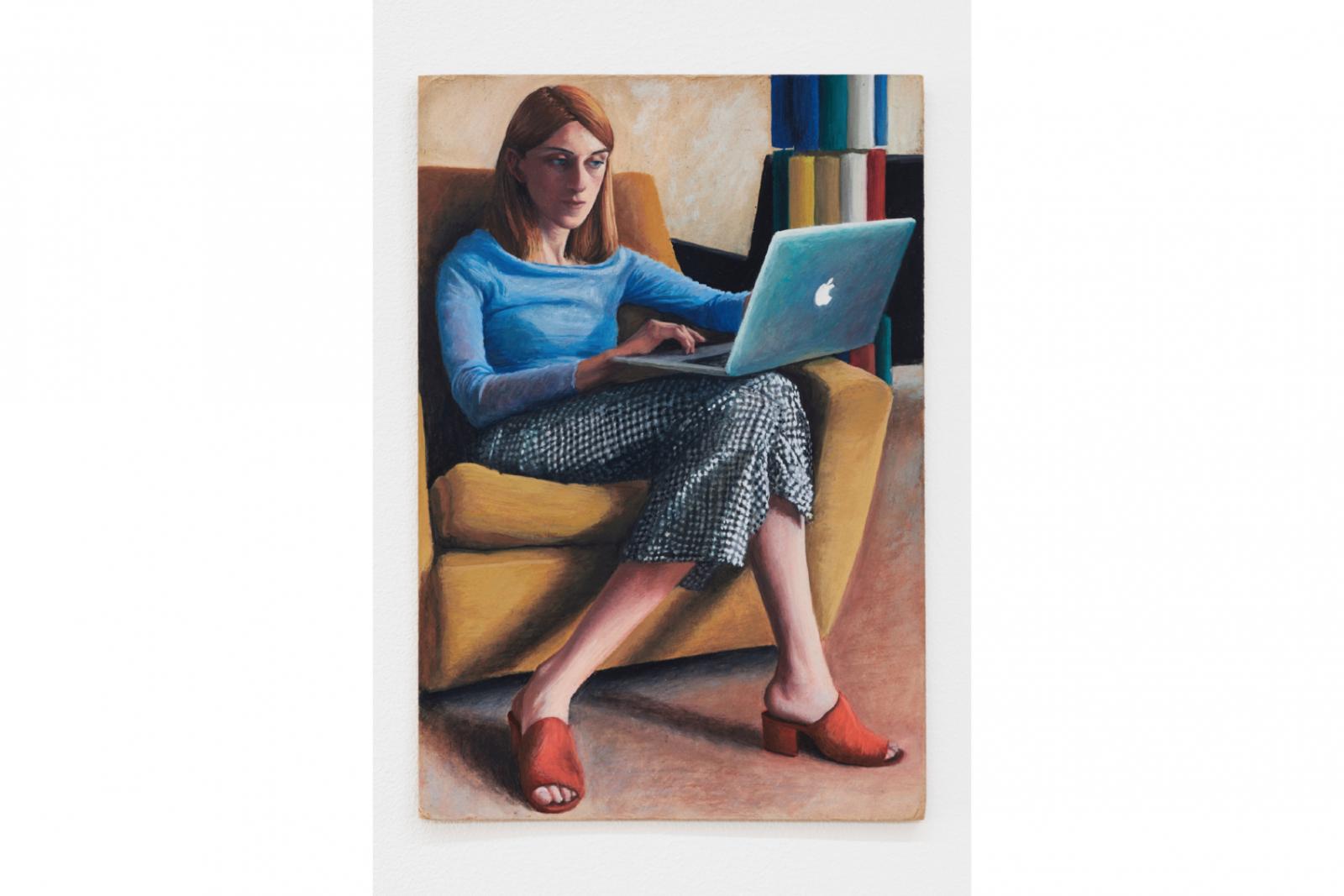

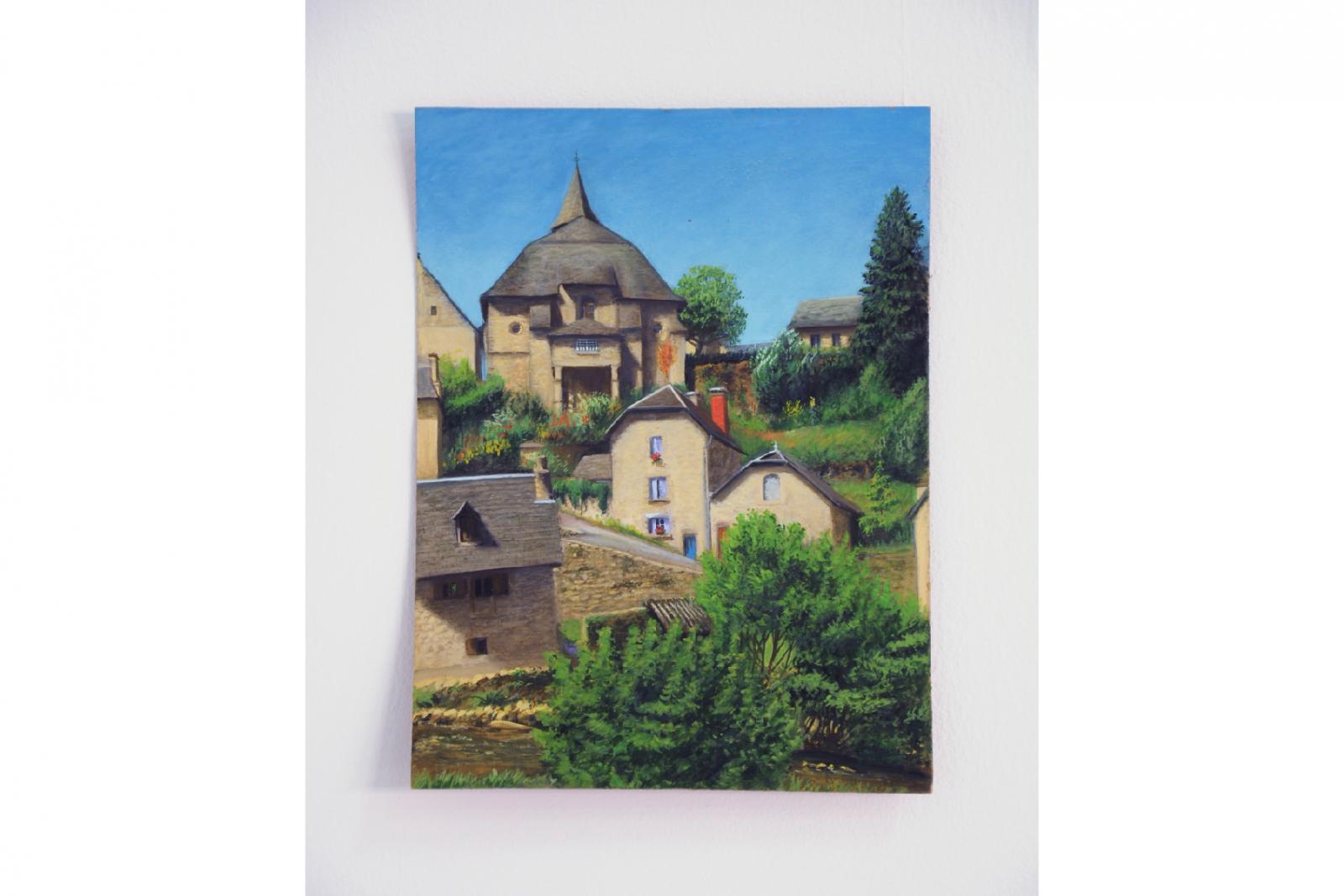

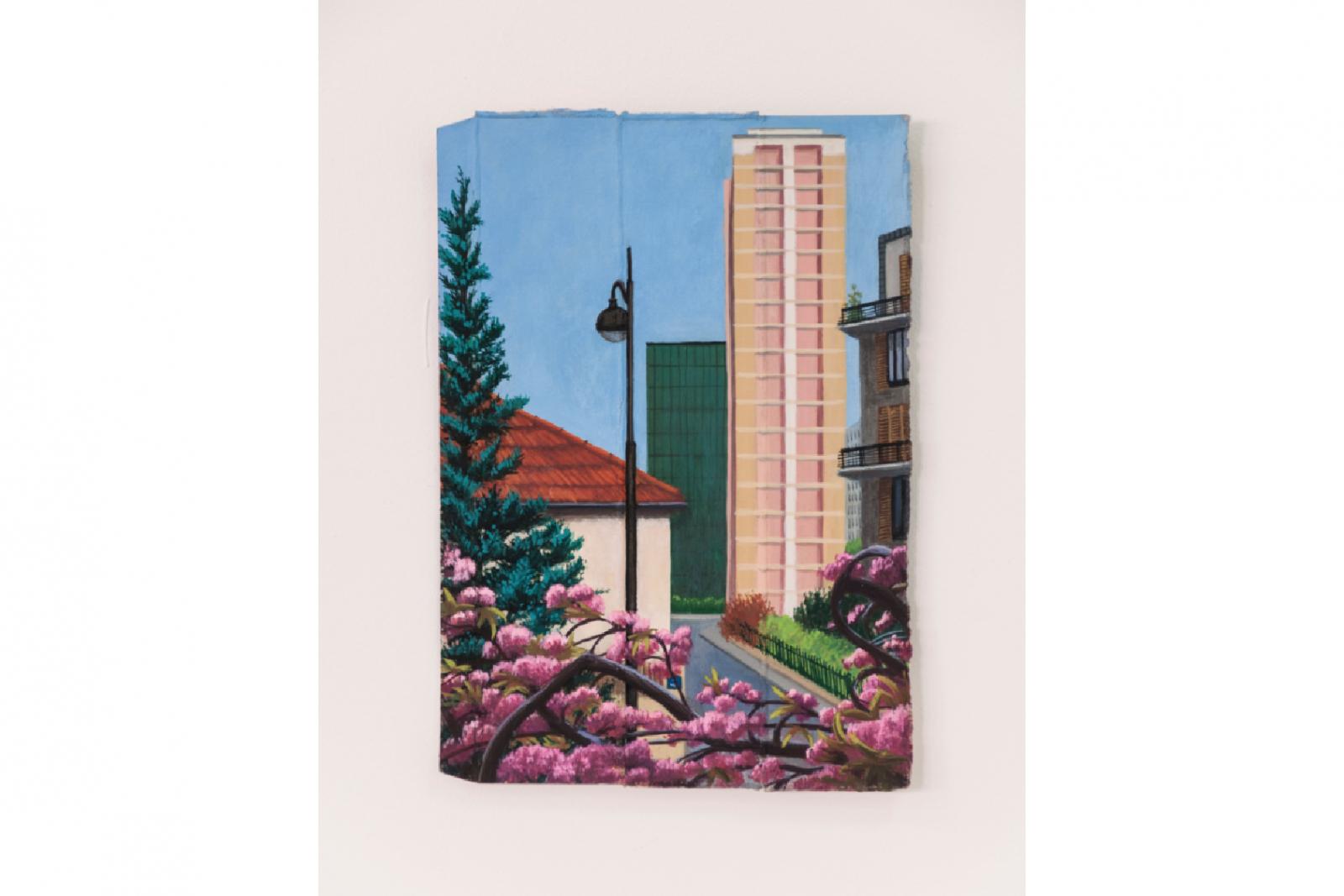

Besides, she does not really care about belonging to that category or to any other for that matter, and, a Millennial through and through, for a while she considered devoting her practice to internet art only. Not only because she was fascinated with the internet but because it seemed simpler, more streamlined, and more humble as well. This she did not do, and there are now real paintings she consequently exhibits in France, Germany, Korea, the United States, England, Norway, Switzerland, and Hong Kong. Sartor’s painting is highly figurative, executed in very small formats, preferably on salvaged cardboard supports (the environment is a Millennial obsession).

Sartor feels compelled to execute perfectly––and above all never frame––the scenes that appear on these small surface pieces saved from the shredder, giving them a curious, imposing presence similar to the one emanating from those small Renaissance portraits made of enamel on copper.

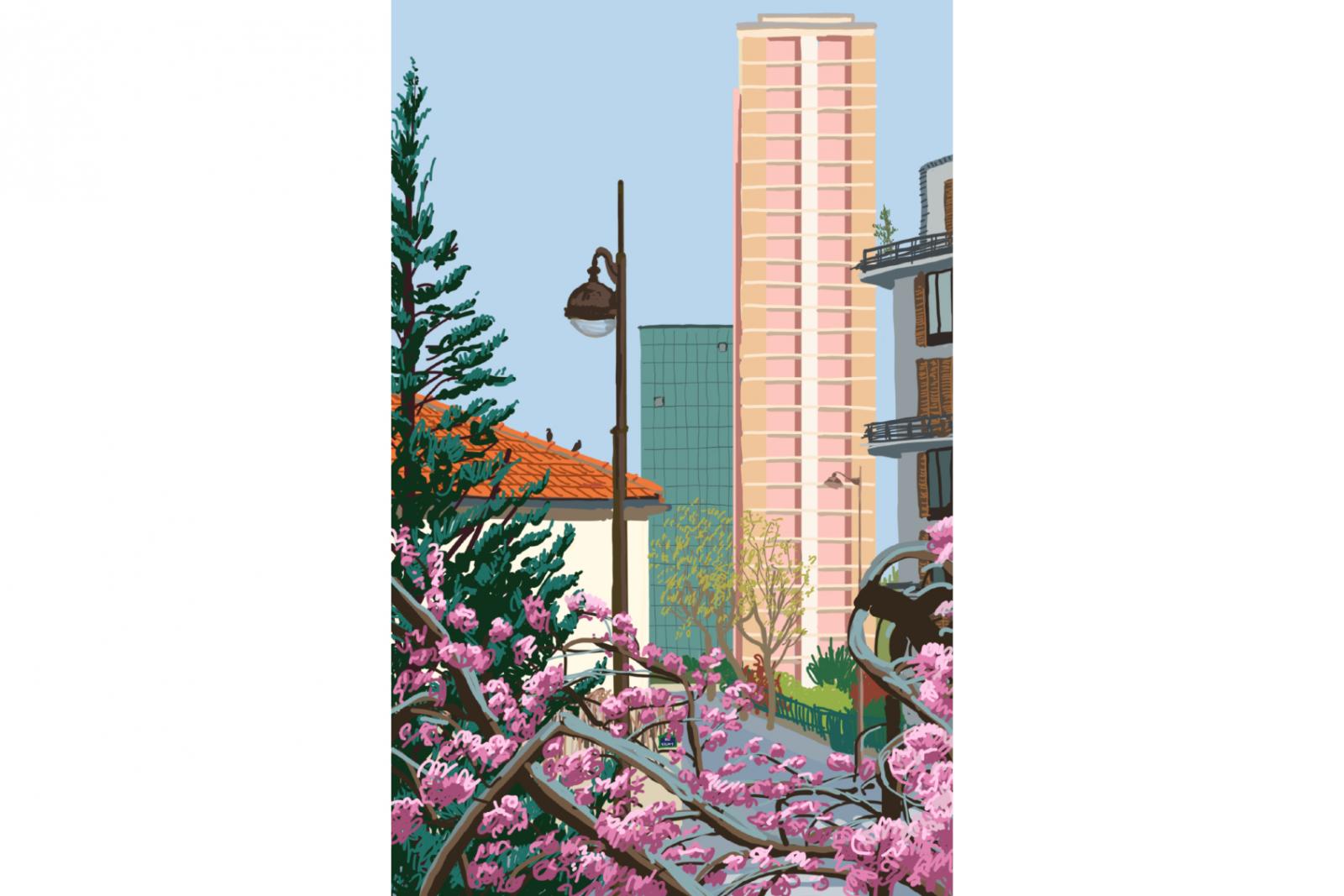

There might be a certain logic in painting on very small formats: Postwar American Abstraction enlarged its formats to measure up with billboards and the silver screen; today’s painting, after all, has to contend with iPhone screens. Because her intent clearly lies with the exploration of painting, few subjects seem to escape her attention, yet regardless of whether these are landscapes or portraits, she needs a true connection with that subject. She works from nature or photographs that she either shoots or finds online and represents actual scenes, even if these are sometimes artificially yet perfectly composed. A Millennial attitude: no matter whether the facts are real, the emotion is true. Often composed with the help of a myriad photographs, her portraits acknowledge slight body distortions, adding up to the strange scenes in which youths often check their iPhones.

She mentions Cézanne and Monet, who came back to the same subjects over and over again, because she too has often “redone” the same image. She speaks in the same inspired way about Mondrian because he relentlessly painted his blue tree before moving on to geometrical abstraction. Like other Millennials she is persuaded that the avant-garde is a closed subject and that the pursuit of the new is not indispensable anymore to a serious visual art practice, and that it would be stupid to imagine a progress for the history of forms––like them, she is evidently wrong, but these are the rules in force nowadays. Like them, she views art history as a kind of mood board from which to pick up this and that from so-and-so and create sophisticated collages. Like them, she imposes her own pecking order on the organization of her sources and influences, where the Mona Lisa would be treated in the same way as a pastry from Pierre Hermé or as a pattern on a dress. But Louise Sartor cannot hide her fascination with painting and its history––here perhaps lies her difference––she admits to a recent obsession with Agnes Martin and on occasion paints with an iPad, yes, just like David Hockney, but she explains this is just a sketchbook for her, and once again an irreplaceable, streamlined solution. With the Samsung tab, she’s got a support and an infinite color palette available in all situations; after all, the screen is pretty much the same size as her paintings.

––Eric Troncy