Paloma Varga Weisz

Glory Hole

Paloma Varga Weisz (1966, Mannheim)

Thank You: Sadie Coles HQ, London; Gladstone Gallery, New York, Brussels, Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht.

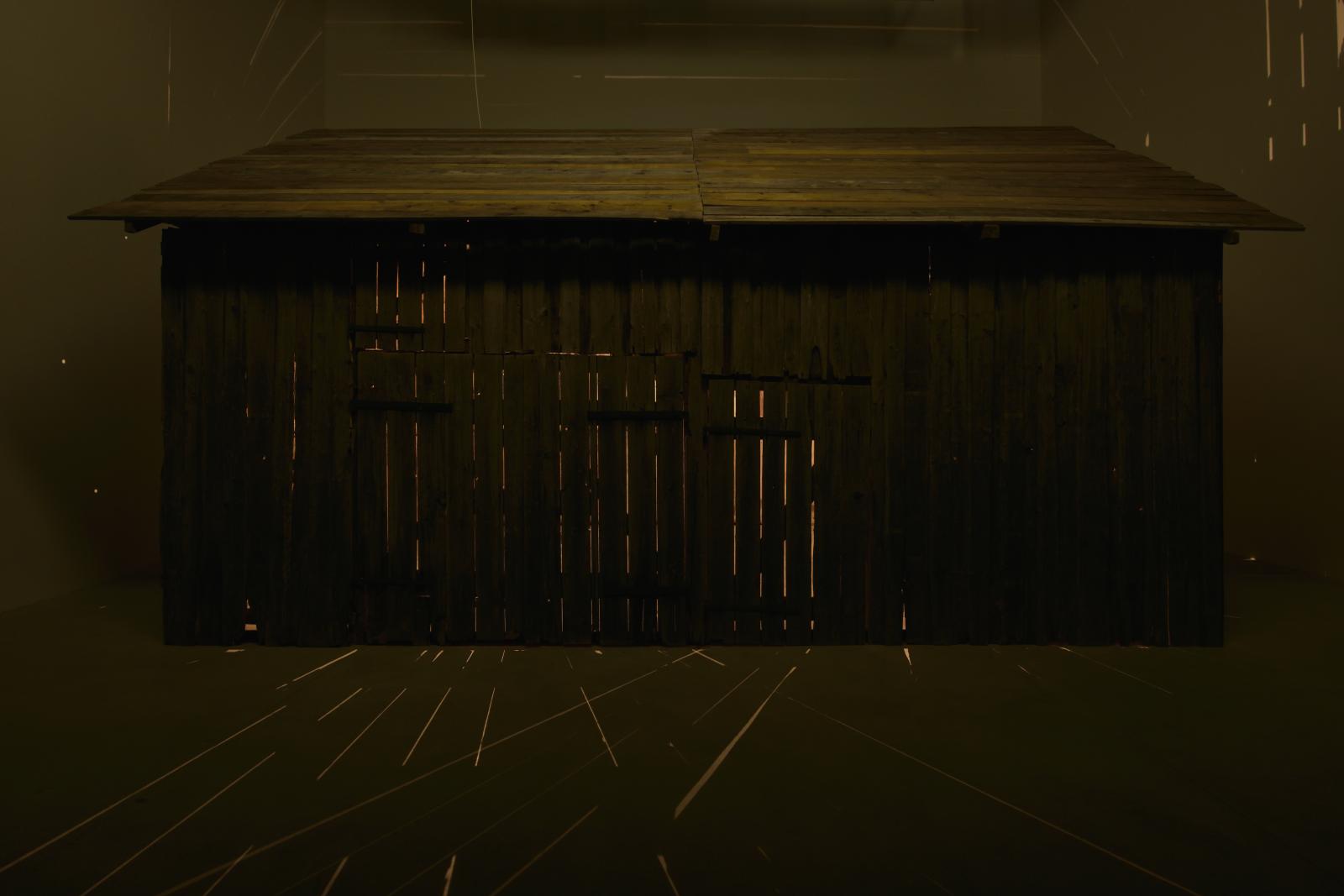

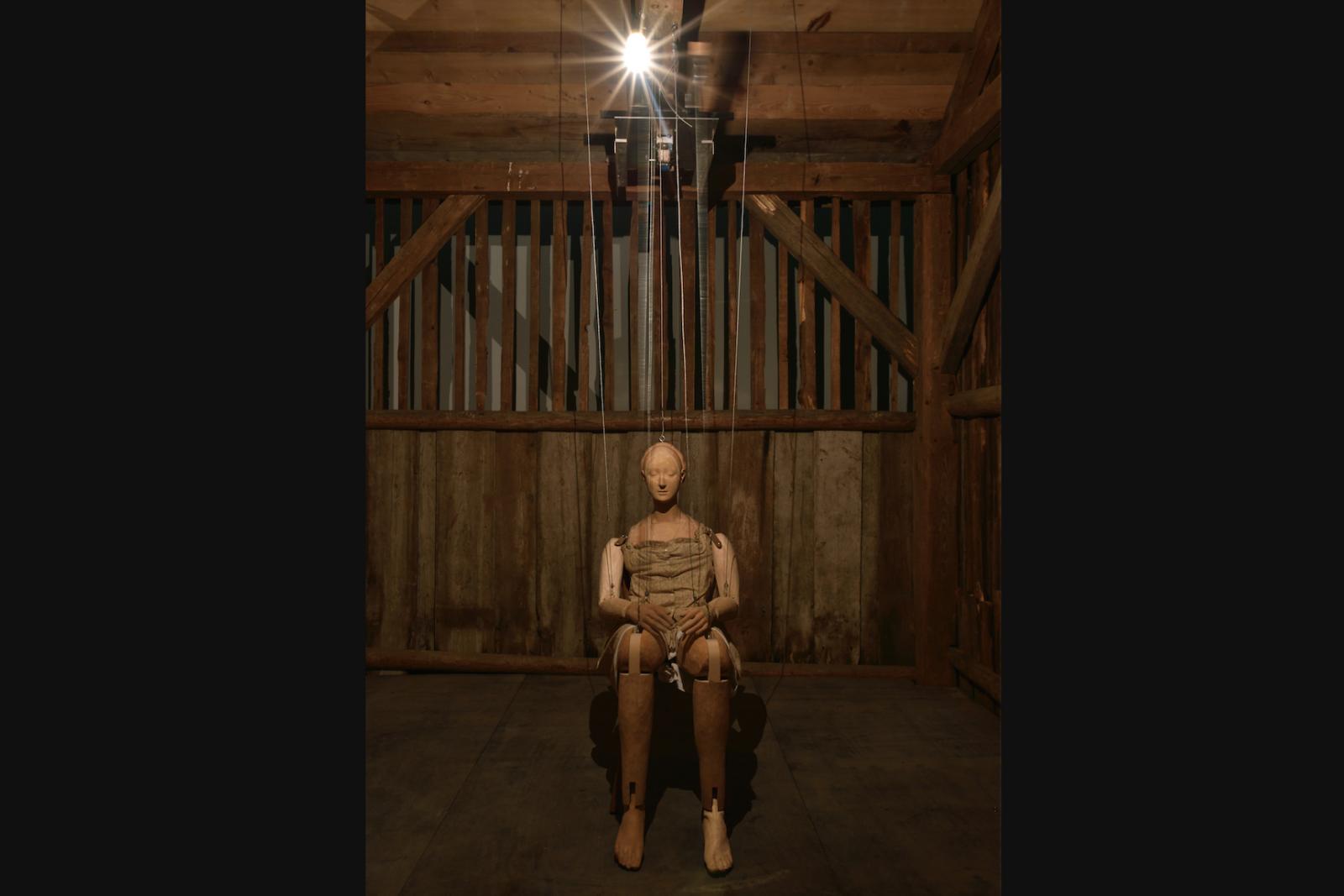

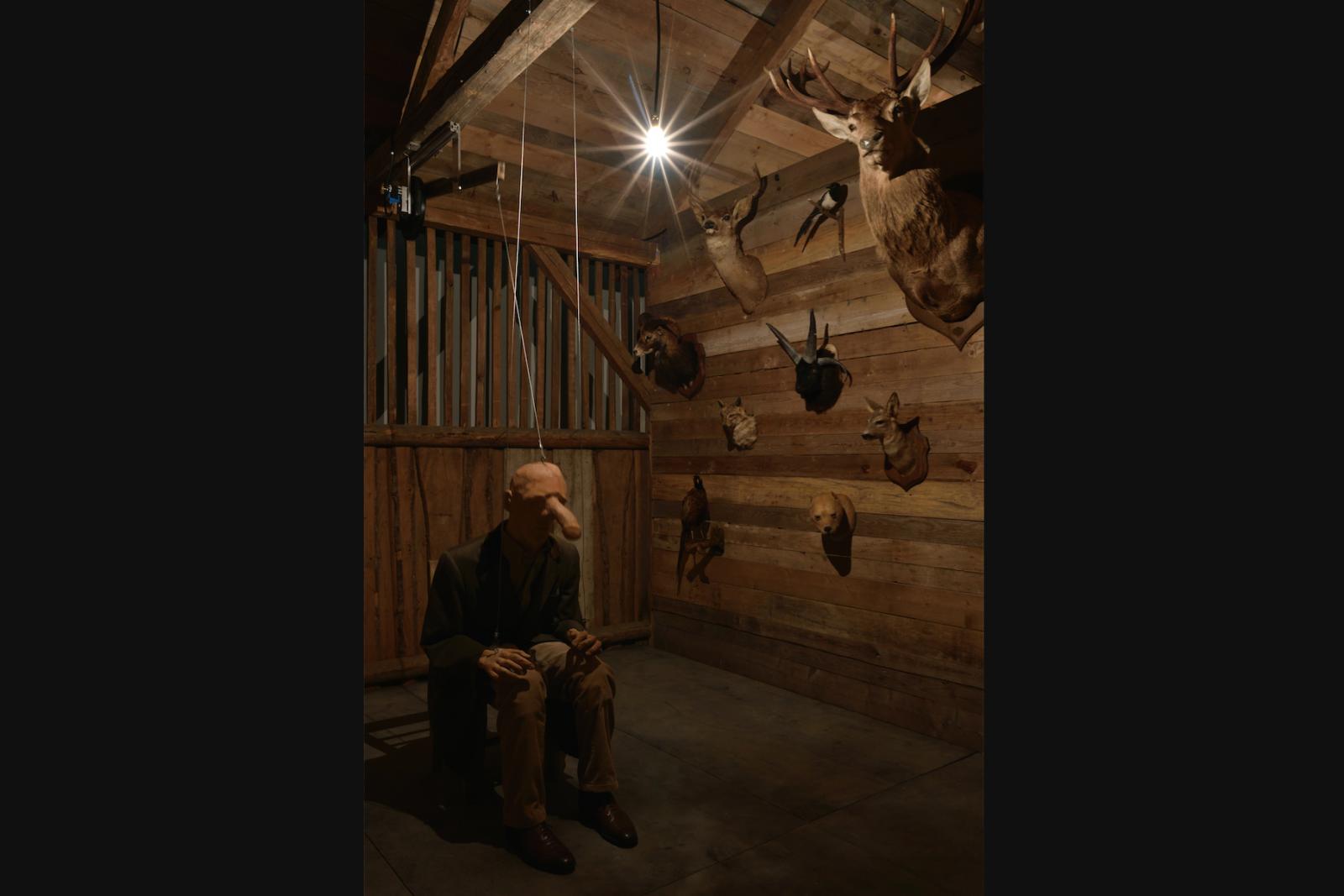

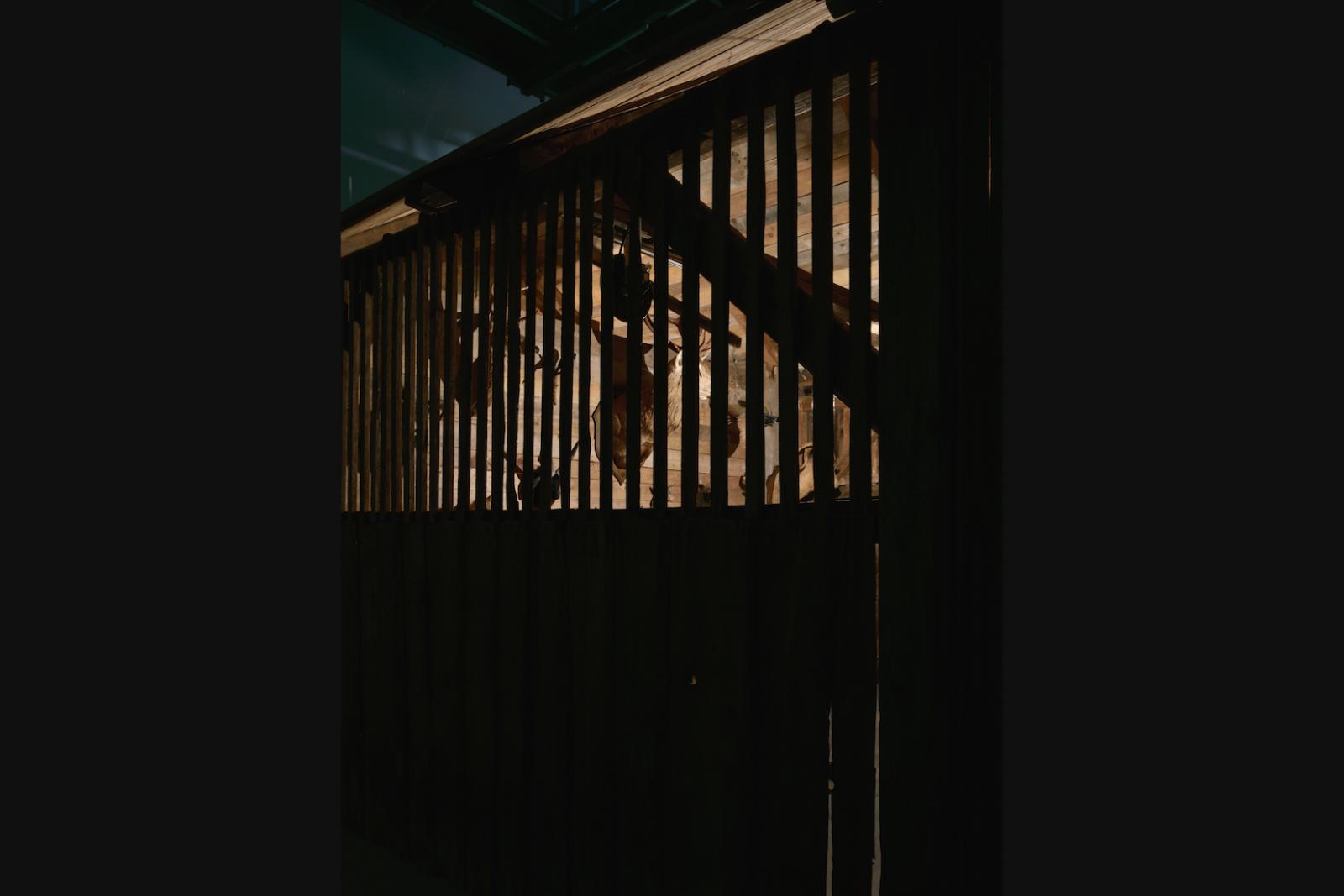

Glory Hole, Paloma Varga Weisz's largest sculpture to date, was first shown at the Salzburg Kunstverein in 2015. It consists in a wooden hut the artist found in the Austrian countryside, two articulated, animated anthropomorphic wooden sculptures, a set of taxidermied animal heads and two taxidermied baboons (1). The whole sculpture is presented in a room plunged into darkness, lit only by the rays of light passing through the gaps between the ill-fitting boards of the cabin, whose interior, separated into two rooms, is not physically accessible to the viewer. The scenes set up inside the structure are only accessible by basically gazing through the openings created in the wooden boards by the absence of knots. Because the artist has titled the installation Glory Hole, what seems to be suggested is that using these orifices to satisfy a visual curiosity may find, right here, an equivalent to the sexual acts for which glory holes are the instrument. Moreover, the anonymity of protagonists engaged in sexual acts by way of glory holes suggests that the spectator too is a stranger to the work he looks at; in any case this title inevitably hints at a "sexualization" of the very act of looking (here, at an artwork), which can be understood as a theatrical spin-off of the scopophilia theorized by Sigmund Freud (the pleasure of possessing the other through the gaze), of Lacan's "scopic gaze,"or of the links that unite eroticism and the eye in George Bataille's Story of the Eye (1928).

Born in 1966 in Mannheim, Germany, Paloma Varga Weisz studied woodworking and its traditional techniques for three years (1987-1990) at a small school in Bavaria, before attending the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf for eight years, starting in 1990—that is, at a time when avant-garde art was making a point of establishing strong boundaries with crafts. At the Kunstakademie, where it was suggested that she should forget everything she knew, she studied in Gerhard Merz’ studio (2). As an artist, Merz was advocating for an art "that makes no false promises to the viewer," with a simple creed: "Proportion, color, light, these are the naked weapons of art. There is nothing more to it. Art as a necessary form of application, grammar within a defined horizon." (3) As Paloma Varga Weisz said, "I think he was like an antipode to me. And I was like growing up on his side, in being against him. He was like a father, where you have to grow up in being the opposite of what he is saying. And I think this was a chance for me that I took this position as a chance to develop something in my mind." (4)

Glory Hole probably does not make "false promises to the viewer" but opens up possible narratives—and food for thought—to those who know how to appreciate it. Installed in this sort of wunderkammer—these cabinets of curiosities that scorn the banal and tolerate only the unique—its two characters seem to be both the subject of a scene and also absolutely disconnected from it, or perhaps, to face them with an exorbitant serenity. Though they are animated and as much as they are engaged in meaningful actions, they express no specific emotion while spreading and closing their legs (for the female character) or waving its penis-like nose (for the male character). The intense dramatization of the décor (the darkness, the board cabin, the taxidermied animal heads on the wall, the monkeys on the floor...) is thus opposed to the characters’ impassivity, between hyper presence and hyper absence: Varga Weisz’s work takes shape in this tension, this irresolute space. In this theater, she undoubtedly embeds biographical elements: the two characters awaken the memory of the wooden dummies or the articulated figurines that can be made to assume the various postures used to learn how to draw the human form. Here they have become (mechanically animated) puppets that recall Pinocchio (a feeling exacerbated by the size of the male character's nose, which is enlarged and looks like a penis), the little creature whose father Gepetto is a carpenter, who loves his puppet like the son he did not have. Paloma has never made a secret of her father’s career and life influence on her. Feri Varga, a Hungarian Jew born in 1906 who came to Paris in 1924 to study art was on the Nazis’ blacklist. He fled to the south of France and became friends with Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso (therein lies the origin of Paloma's first name), Jacques Prévert, and Henri Matisse. “A lot of artists have private stuff in their work and, because of that, I perhaps have my doubts as to what really is private. Makers and their stories are just ingredients. The work is an independent thing, and the connection to the viewer is another independent thing, because you always bring your own story into the viewing of a work.“ (5)

— Éric Troncy

- The work of inventorying natural heritage has made it possible to define whether species are threatened or not. Thus, nature conservation organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature have been created and international agreements implemented, including those of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), aimed at regulating the trade of protected species. As data is regularly updated, species that were once considered non-endangered are now prohibited from being collected. Thus, specimens in museum collections that were caught before their inclusions on those lists are now subject to strict regulations. Natural science collections are thus responsible for the conservation and the transmission of this heritage.

The exhibition of Paloma Varga Weisz ‘s artwork Glory Hole thus makes it possible to show to viewers species that are protected under CITES or by decrees and are difficult to observe in any other way.

The animals presented (with the exception of authorized hunting trophies) have died of natural causes and have been prepared by certified professionals, in accordance with current laws.

Where applicable, the animals have an EU certificate under CITES legislation. All required authorizations for their transport and exhibition have been obtained. - In 1987 Gerhard Merz had a solo exhibition, Inferno, at the Consortium Museum (December 15, 1987- January 30, 1988)

- Gerhard Merz, quoted by Herbert Molderings, exhibition catalog Kunsthaus Bregenz 2007.

- Dialogue talk

- Anna McNay, "Just a small Piece of Wood and a Knife: A Conversation with Paloma Varga Weisz," in Sculpture Magazine, November 16, 2020